Carrey’s first straight role.

It was simply majestic,

And unfairly panned.

Category / Drama

Film review – Frantz (François Ozon, 2016)

Set primarily in Germany in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, François Ozon’s latest film is an emotional story portrayed almost entirely in black and white. It revolves around Anna (Paula Beer), a woman who is living with the parents of her lost lover and supporting each other in their collective grief. That man is the titular Frantz (Anton von Lucke), who we learn has lost his life in battle during the war. When a Frenchman by the name of Adrien (Pierre Niney) shows up at Frantz’s grave to give his respects, he tells them of his close friendship to their mutually lost friend.

Ozon is something of a prolific filmmaker on almost the same level as Woody Allen. Since his celebrated debut feature length film Sitcom in 1998, he has written and directed sixteen films, amongst them the critically acclaimed Swimming Pool and the highly successful Potiche. Yet Frantz is, by all accounts, a departure in style for him and sees him in relatively unfamiliar territory with a historical war drama.It is based on the play ‘L’homme que j’ai tué’ by Maurice Rostand. Before writing his script, Ozon was unaware that the play had already been adapted by legendary filmmaker Ernst Lubitsch as the film Broken Lullaby in 1931, though when he watched the film he realised that it was a completely different treatment to the direction he wanted to go with Frantz. He wanted to give the focus of the film to Anna, who was on the losing side of the war, providing more empathy to her as the central character.

There is an interesting chemistry between Beer and Niney, both of whom are playing extremely complex characters. They share this individual that has had a huge affect on their respective lives and begin to grow closer. Providing convincing characterisations of such conflicting emotions is a challenge both rise to and it is this that elevates the film above being a wartime drama.

It was amazing to learn that this was Beer’s first performance acting as a French-language character. Many successful actresses couldn’t achieve what she has here in their first language let alone their second one. She revealed in a post-screening discussion that she had to learn and develop the script twice. Initially she developed the emotional responses to the words in her native German, before relearning the entire segments in French to ensure her delivery wasn’t lacklustre.

This is a truly moving film that gives an interesting point of view to the fallout from war that hasn’t often been explored before. Superb delivery from the two complex central characters means this comes highly recommended.

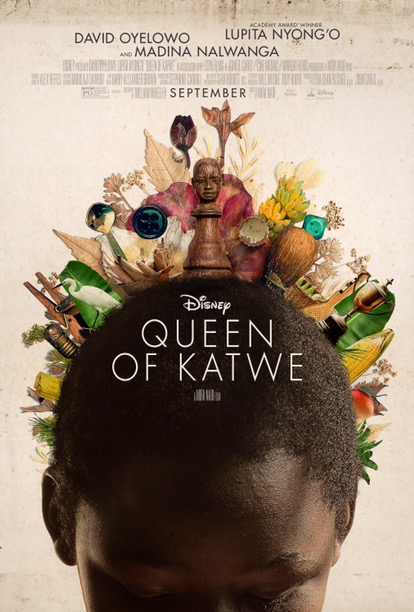

Film review – Queen of Katwe (Mira Nair, 2016)

Walt Disney Studios may have a long history of releasing underdog sports films, but their latest live action is nothing like any of its predecessors. In fact, it’s a breath of fresh air, as the crowd discovered tonight at the UK premiere.

Set and filmed almost entirely in the slums of Katwe in Uganda, the film tells the story of Phiona (newcomer Madina Nalwanga), a child who learns to play chess under the mentoring of missionary Robert (David Oyelowo). Much to the initial dislike of her mother Nakku (Lupita Nyong’o), she excels at the game and quickly starts competing at international competitions, giving her the opportunity to escape from certain poverty.

At the heart of the creation of the film was Mira Nair, the female director who knows Uganda inside out (she met her husband whilst researching the film Mississippi Masala in 1989). She spoke prior to the screening of the importance of filming the entire film in Uganda and leaving a positive message about the country outside of the anti-colonialism that is a constant recurrence in films about Africa (though A United Kingdom is very good too!). There should be no worries that this is a risky move for Walt Disney Studios.

The triangle of central characters played by Nyong’o, Oyelowo and Nalwanga are what helps the film achieve so much. Whilst Robert acts as a much-needed father figure to Phiona, he in turn proves antagonistic to Nakku, a mother who is keen to protect her second-eldest daughter for fear of her making the same mistakes as her elder sister Night.

Indeed, it is Nyong’o’s turn in the film that, for me, makes it a true triumph. As the protective mother to a daughter she fears is getting into something too unfamiliar, the result is a strong-willed role model for black women (as she is in real life). This is sadly in short supply in the modern cinematic landscape. This is a topic that will doubtless be explored in BFI’s promising Black Star programme throughout October 2016.

Festival director Clare Stewart, director Mira Nair and stars David Oyelowo and Lupita Nyong’o at the UK premiere

Nair does a great job with the telling of a captivating story throughout the chess matches. This is tricky territory for a filmmaker. If too long was spent explaining it, there’s a risk of boring your audience. Spend no time on it at all and you lose the core of the story. Get the tone wrong and you look completely foolish. Time was spent making sure that the metaphorical importance of the game was reflected in the development of Phiona as a character. It works perfectly.

It was a joy to see East Africa looking so vibrant, brought to life with some beautiful shots and an uplifting story. A total triumph.

Queen of Katwe is in UK cinemas now and can also be pre-ordered for home-viewing.

Film review – Julieta (Pedro Almodóvar, 2016)

The latest film from Pedro Almodóvar, Julieta, is a stunning interwoven story of mystery and intrigue that the director takes great care in unraveling for our viewing pleasure.

Centred around the titular character, we are introduced to Julieta as she plans to move from central Madrid to Portugal with her boyfriend Lorenzo. However, a chance encounter with a friend of her daughter causes her to completely rethink her decision. Her daughter, Antía, has been missing for several years and moving will mean any chance of reconnecting with her will be lost. She opts to stay behind and rent an apartment in the last known address that her daughter could contact her. She fills her time hand writing her thoughts on the events that led to her daughter’s disappearance, which play out in the form of a long flashback that makes up the bulk of the film.

It is an adaptation of three stories by Alice Munro taken from her 2004 award winning book Runaway, which Almodóvar first hinted at in his brilliant 2011 horror thriller The Skin I Live In via a Spanish-language version of the book being prominently read by one of the central characters.

The music in Julieta plays a critical part in setting the tone, switching it from serious drama to something slightly more sinister. It borders on sounding like a horror film at times, with the implied effect of hinting that whatever story has been revealed thus far still has more secrets within.

The success of the film ultimately lies on the two actresses who portray Julieta at various times through it her life. Fortunately, both Emma Suarez and Adriana Ugarte provide brilliant turns as the older and younger incarnations of Julieta, respectively. They are very different takes, resting either side of a devastating incident in her life. It works perfectly well and the change is handled with a certain elegance that ensures buy in from the audience.

Some ardent Almodóvar fans have been disappointed with his recent output, with some pointing to airplane-disaster-comedy I’m So Excited as an indication that he’d lost his edge. Any doubts about how seriously he takes his work can be put to bed with Julieta – a beautiful work of art and a must see for anyone with a penchant for high quality cinema.

Julieta is available now on DVD.

Film review – Captain Fantastic (Matt Ross, 2016)

Captain Fantastic is not the latest in the never-ending chain of Marbel superhero films. Nor is it a profile of former Liverpool captain Steven Gerrard, who is fantastic for about half of Liverpool and few others.

No, despite the title, Captain Fantastic is the directorial debut full-length feature from Matt Ross, better known as Gavin Belson from Silicon Valley. Beyond the superficial veneer of a twee, heartwarming, quirky indie flick, there is something a little more substantial and special at work here.

Viggo Mortensen takes the lead role as Ben Cash, a father raising six children as an only parent after his wife is hospitalised with bipolar disease. Nurturing them off-grid in a sort of wilderness commune, he is forced to bring them back into society when he receives the news that his wife has committed suicide. The journey to New Mexico for the funeral forces him to re-evaluate his choices in bring up his children, exposing them all to a world they have shunned.

Many of the greatest films to grace our screens have us questioning are inner-most philosophies. Whilst this isn’t likely to be considered an all time great, it does push the right buttons in its ability to be thought-provoking. The six children are for the most part absolutely happy, well educated, physically fit individuals that seem to have had no ill-effects from the unique brand of homeschooling afforded by their father Ben. The portrayal from them is so convincing that I was left seething when their families began to interfere and bring them back into “normality”.

One thing that was very evident was the chemistry between the six children and Mortensen. George MacKay takes centre stage as eldest child Bo on the brink of leaving for college but struggling to find the best way to tell a father to whom he is completely devoted. Samantha Isler and Annalise Basso are great as the inseperable pair Kielyr and Vespyr. Charlie Shotwell, Nicholas Hamilton and Shree Crooks all have extremely bright futures in the industry, the latter of the three having a charismatic charm that brought an element of hilarity to everything she said.

It is this sense of comradery and unbreakable dedication that is essential to the success of the film and without it we’d be left with nothing. Thankfully it’s here in abundance.

The music from Alex Somers (Sigor Ros producer) plays into the mood perfectly, reflecting the subtle charm of the visuals on screen. It’s non-offensive but beautifully balanced.

A must-see, feel-great film.

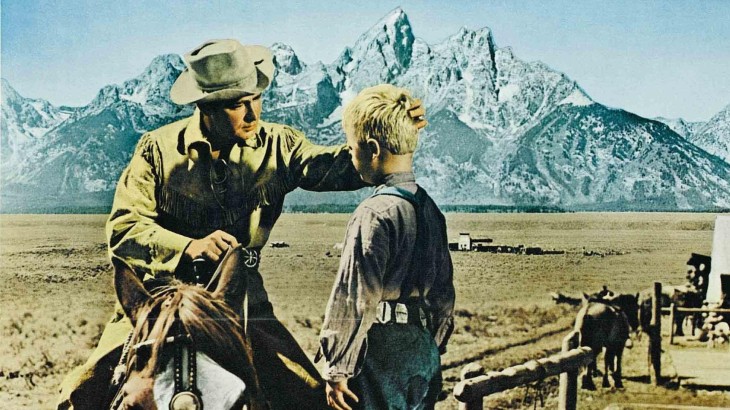

Film review – Shane (George Stevens, 1953)

I’ve never been a huge fan of Westerns. It’s a slight bugbear of mine and I hate to be so sweepingly dismissive of an entire genre, but until recently they’ve always seemed so formulaic and lacking in unique characters.

That’s not to say I don’t have many fond memories of Westerns. My grandfather was a huge fan of any films with cowboys in. Growing up, I lived away from most of my family and so getting to my grandparents’ house was a long journey that would usually have us arriving in the early afternoon, by which point my grandfather would often be settling in to watch a good Western. At the time, the subtleties of the character development or the most intense of standoffs was undoubtedly lost on my pre-teen self.

With the trusted Master of Cinema label now lovingly releasing a select few Western films (with the typical smorgasbord of bonus material to help put the films into context), I’m giving the genre a second chance, if nothing else to prove my smarmy little 10-year-old self that he was wrong all along.

Shane tells the story of the titular hero, played by Alan Ladd. As the opening credits play out, he rides into a small isolated town in Wyoming to meet the Starrett family. He has a mysterious past but quickly wins their favour before the father Joe (Van Heflin) invites him to stay on their property to help out on the ranch.

Over dinner, he learns that the entire town is being terrorised by Rufus Ryker (Emile Meyer) and his gang, who are driving out families one-by-one to gain total control over the land in the area in order to better herd their cattle.

Thus, the story plays out with Shane and Joe forming a stern partnership to rally against the gang and save the town for those families already settled. As the conflict escalates, Shane emerges as the classic lone gunman hero in which the whole town’s hopes lie.

Whilst the story itself is quite familiar, befitting of any good cowboy or samurai film, director George Stevens gets away with the over-idolisation of Shane as the all-American hero by the inclusion of the young Joey Starrett (Brandon deWilde). It is through his eyes that we see everything happen. This has one of two effects. Firstly, it allows Shane to be as formulaic as he needs to be by virtue of the fact that the story can be considered as a retelling of the tale through Joey’s memory of the fact. If that doesn’t sit well as an interpretation, then at the very least the saintly actions of Shane can be seen as a means to leave a positive impression on the child – which he certainly does.

He is clearly a man wrestling with the wrongs of his past, and spends most of the film trying to hide this from the Starrett family. When he finally reveals his gunslinging credentials in front of the Joey, he decides it’s time to move on, presumably to the next place he stumbles upon that needs rescuing.

Whether he makes it to that next town is open to interpretation. Indeed, in the final shootout, he does take what looks like a fairly serious wound to the torso. He plays this down for his final leaving speech for Joey, but as he rides off I couldn’t help but wonder whether he was going to survive. After all, he’s spent the best part of two hours putting a brave face on for every other aspect of his life – he certainly wouldn’t let on to Joey that he was about to die.

The romantic subplot between Shane and Joe’s wife Marian (Jean Arthur) adds an interesting subtext to the situation. Clearly she is pining for him, and her interest is underlined in every scene they share. It feels a little shallow, and does nothing for Marian as a character as she follows every stereotype in cinematic history. Alas, it was typical of the time and her only purpose is to add some sex appeal to Alan Ladd’s handsome hero.

Shane may be a typical Western, but it is a fine and pure example of the genre that is rightly being held up as one of the best of its kind.

[Note 1] The second screenshot in this review is how the film should look on your widescreen television, with black bars down the left and right sides of the picture. This is due to the aspect ratio used (1.37:1). There is a second aspect ratio available on the disc, though as Adam Naymar explains in the booklet note “Don’t Fence Me In” this is a controversial version of the film. I’ll let you read it for yourselves should you make the purchase.

[Note 2] Below is the theatrical trailer for Shane. It is proof that cinema goers in 1953 cared not for spoilers, as the critical climax of the final scene of the film is included. Quite why this was done is a mystery to me as it completely ruins the entire film, but since the film is now 63 years old I don’t feel it is fair to be angry towards me for including it in this article. After all, I’ve given you fair warning…

Film review – A Bigger Splash (Luca Guadagnino, 2016)

A Bigger Splash tells the story of Marianne Lane (Tilda Swinton), an ageing rock star taking a resting vacation on the remote Italian island Pantelleria with her boyfriend Paul (Matthias Schoenaerts), a filmmaker. Their vacation is disrupted when Marriane’s larger-than-life ex Harry (Ralph Fiennes) arrives with his daughter Penelope (Dakota Johnson).

Watching A Bigger Splash is a little like watching a car crash in agonisingly slow motion. As the tensions rise and tempers are frayed, you see the action unfolding and there’s nothing you can do about it. Even though you want to look away you just can’t.

An interesting choice attributed to Swinton herself was that Marianne is recovering from an operation on her vocal folds. It means that her abundant acting abilities risk going to waste. This isn’t the case at all. Indeed, that she is able to command her scenes whilst not even speaking highlights her presence in front of a camera. Her frustration at not being able to shut Harry up is evident. This, mixed with Paul’s desire to not be drawn into arguments and Penelope’s apparent disinterest in just about everything, means Harry is able to be the centre of attention at all times, much to the bemusement of the three people whose lives he is engulfing.

It’s a tremendous performance from Fiennes. He is most certainly an annoying person to watch on screen, let along imagine being on holiday with. He’s a tragic man desperate to avoid the realisation that nobody cares anymore. We all know someone like Harry in our lives, but none of us like him. Unfortunately, whilst the performance is fantastic and it plays out beautifully, it doesn’t necessarily make for great cinema. Achieving a cinematic goal doesn’t justify it.

One thing this film shares with La Piscine, the 1969 French film on which this is based, is the gratuitous nudity. It didn’t really feel integral to the plot, and lacked any kind of eroticism that it may have been angling for, feeling instead to be overly sleazy.

The political setting didn’t really give any edge to the film either. Set amid a backdrop of illegal migrants landing on Pantelleria, it just felt like a shallow attempt to date the film without adding much to the plot. This could have been rectified if we’d seen the migrants sooner, but by the time they were first mentioned it felt like an irrelevant afterthought.

The film also feels about twenty minutes too long, with the action seeming to reach a climax only to drag on far beyond the point it held my attention. As with all car crashes, it’s not very enjoyable to watch. The elements are all there – great acting, beautiful scenery, fantastic plot development – it’s just that the overall effect doesn’t deliver on its component parts.

A Bigger Splash is out at cinemas now.

Film review – Spotlight (Tom McCarthy, 2016)

There are obvious paths to go down to tell a story about victims of child abuse. This film eschews the story of the individuals who have suffered the abuse, instead concentrating on the journalistic team that fought hard to uncovered the abuse. It deliberately attempts to portray just how difficult it was to reveal the truth about something when nobody wants to listen and everybody involved is trying to cover up what has happened. It is an effective but devastating success.

The title of the film is taken from an investigative journalistic unit that tackles stories it deems of necessary interest to the readers of The Boston Globe. In 2002 it published an exposé on Roman Catholic priests in the Boston area, offering evidence of not only child molestation and rape, but also of the systemic cover-up of the evidence by the church. The truths they found were horrific in both nature and magnitude.

Whilst the movie is truly an ensemble piece, there are three wonderfully nuanced performances that help make this film so effective.

The first comes from Stanley Tucci as the attorney Mitchell Garabedian. Tucci is a really special actor and he’s in fine form here. Garabedian has represented innumerable victims of the abuse and each time has been unable to affect change, with critical documents being suppressed by the church. Reminiscent of his role in Margin Call as Eric Dale, he is a man with knowledge of the wider secret dying for those around him to find out what’s truly going on.

A smaller but memorable turn comes from Neal Huff as Phil Saviano, head of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. Based on a real person going by the same name, he makes the most of his limited screen time when he provides a harrowing monologue the first time he meets the Spotlight team. A frustrated picture of a man that likely represents the emotions felt by each and every survivor.

The finest performance, however, is from Michael Keaton as the Chief Editor of Spotlight, Walter “Bobby” Robinson. Throughout the story Bobby is a man wrestling with his conscience. He knows that to make the story as effective as possible he needs to wait for all the facts to be in place and make a thorough, damning article that cannot be ignored. However, doing this means sitting on the information whilst the abuse continues in the city. Late in the picture when he finds out he was actually tipped off about the scandal twenty years previously, he must conclude that he is finally bringing justice to the city despite potentially having the power to prevent generations of systemic abuse. Keaton nails it, reminding us all once again how great it is to have him back on the big screen in a role of substance.

I’m surprised Mark Ruffalo and Rachel McAdams have been selected for an Oscar nomination ahead of those they share the screen with. Fine actors though they are, it must have been a tough call to select two from a long list of solid performances. Ruffalo seemed to be holding back slightly, though that was perhaps a deliberate choice I didn’t pick up on fully.

It is rare that a whole audience is left in absolute silence at the end of a screening, but even on a busy Saturday afternoon there didn’t seem to be anyone that felt anything other than stunned. The reason for this was a devastating list of all the locations they have uncovered scandals in since the publishing of the initial article in 2002, firstly in the USA, then globally.

For this reason the film is now serving the same purpose as the original article: to shine a spotlight on a diabolical scandal that should have been eradicated decades ago. It is possibly the most important film you will see this year.

Film review – Room (Lenny Abrahamson, 2015)

Much more understated in its promotional campaign than its awards season rivals – and a much harder film to describe with any vigor and make it sound interesting – Room is a film that simply needs to be seen. It may not seem it but it’s a wonderful hidden gem, the quality of which will only become apparent once you’ve seen it.

It is a film set in two distinct acts. The first act is based entirely in the room in which a woman known as Joy (Brie Larson) and her five-year-old son Jack (Jacob Tremblay) have been held captive by the mysterious Old Nick (Sean Bridgers). Following their release, they are reunited with Joy’s family and the outside world – a world that has left Ma behind and that Jack has never even experienced. Overwhelmed by their new freedom and affected by their psychological damage, we follow Joy and Jack as they try to find any kind of normality in their new life.

Jacob Tremblay and Brie Larson in Room.

The tiny room is suffocating in its lack of space and the feeling of being trapped is never more convincingly portrayed than when Jack is hiding in his cupboard. Looking primarily from his point of view in this first act, the room comparatively seems quite large – to him it is the whole world as he knows nothing else.

Through the unavoidable depressing nature of the situation, there are moments included that are truly uplifting. Seeing Jack finally open up to a family member is a beautiful moment. Indeed, it is surprising that Jacob Tremblay hasn’t been singled out for his stunning performance as Jack, a child who has gone through an impossible first five years of life. He has either been coached really well or is a true natural.

That said, Brie Larson can rightfully take the praise for her leading performance. Her character has taken the journey from childhood to motherhood within the confines of one small room and has remained strong for the sake of her child. The emotional turmoil is all there to be seen. It is deliberately difficult but equally rewarding to witness.

An early contender for one of my top films of the year.

Room is on general release globally now.

Carol (Todd Haynes, 2015)

The latest Todd Haynes film, his first big screen effort since 2007’s Bob Dylan biopic (of sorts) I’m Not There, has been exceptionally well received by the press and public. An adaptation of the 1952 novel The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith, the film tells the story of the relationship between Therese (Rooney Mara), a young aspiring photographer working in a department store, and Carol, an older woman with a penchant for younger girls. It explores their developing relationship as Carol’s marriage to Harge (Kyle Chandler) deteriorates, and the reaction to their behaviour by those close to them in 1950s Manhattan.

The world has gone crazy for this film. It has already picked up a Palme d’Or nomination (losing out to Jacques Audiard’s Dheepan) as well as two wins at the Cannes Film Festival. It also won prizes at a host of other award ceremonies, and will compete with five nominations at the Golden Globes. One can only presume the Academy Awards and BAFTAs will follow suit.

As such, it’s a difficult film to openly ardently dislike. The source material has been, apparently, a very relevant book to the LGBT community for many years, especially in the USA. I am a straight male British man. The fact I didn’t enjoy it gives rise to an enormous fear that I’m too straight-laced to understand a masterful piece of cinematic artistry. It’s the sort of thing I should like. I just didn’t.

For me, the exploration of the controversy of a same-sex relationship in 1950s America wasn’t enough to save the slow pacing and inherently dull storyline. An easy argument is to think along the lines of replacing either of the lead characters with a man, then ask ourselves “Is this still an interesting plot?”

The more unusual channel on this stance would be to have an older woman befriend a younger man, which would bring more dynamics with social disagreement than the oft-covered “older man with younger girl” scenario.

To think like this, however, is to miss the point. There’s no reason why having a female-to-female relationship can’t be explored at face value whilst also looking at the contrasting views of those around them. The fact is that the two female lead characters’ relationships with those around them wasn’t explored enough to warrant any real threat of anguish and being cast out of society. Conversely, there was no apparent chemistry between the two actresses. My suspicion, having not read the book, is that this was all explored in great detail by Patricia Highsmith and there wasn’t enough scope to cover it all in one standalone film.

I’d describe both acting performances as adequate without being exceptional. The desperation of the situation is only truly realised when Kyle Chandler appears as the scene-stealing husband who evidently fears the rejection by his wife as much as he fears the embarrassment and damage to his social standing. It was only in his scenes towards the backend of the picture that there was any great feeling of scandal.

When Carol is announced as an Oscar front runner next month, I will refuse to eat my words. As someone who doesn’t like this film, I will be in the minority.

Carol is on general release at cinemas in the UK now.