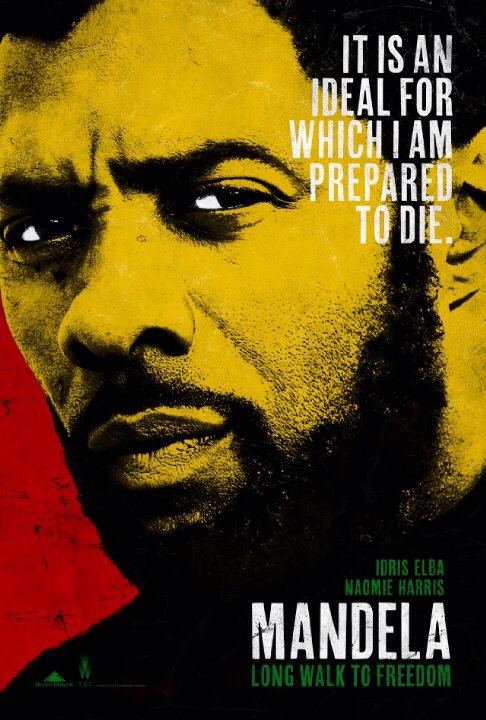

Mandela: Long Walk To Freedom is a biopic of the life of Nelson Mandella, a rich and vibrant story that has been crying out for a big screen adaptation for years. It’s pulled off in great style by director Chadwick. The story becomes even more poignant with the recent news of his passing, but makes the timing of the release of the film perfect.

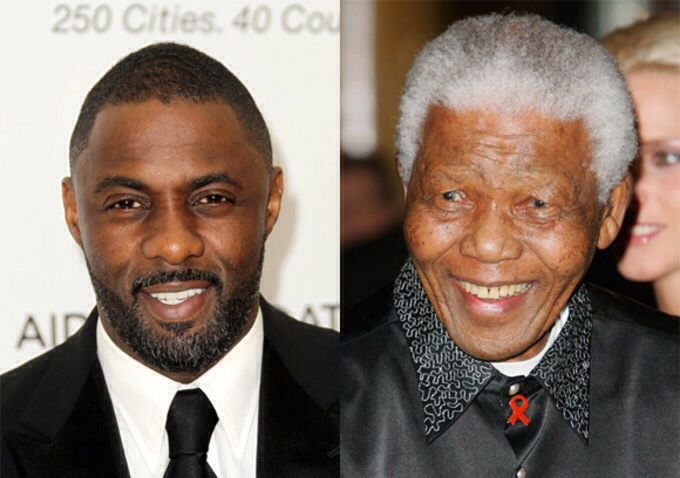

The first thing you’ll notice when the film starts is that Idris Elba, famous for his roles in Luther, Prometheus and more recently Pacific Rim, looks absolutely nothing like Nelson Mandella. Many people assumed there would only ever be one man for the job: Morgan Freeman. Yet, the ambitions of this film were to cover Mandella’s whole life, and the meat of the story required a younger man to take the role. That Elba doesn’t look like him doesn’t really matter; his mannerisms and ability to convey the emotion of this rich story are of far greater importance.

The story moves at a terrific pace – it has to so it can cover everything. At times I wondered whether they could have spent longer on certain sections, and maybe a two part film would have been more suitable (this worked to great effect in Steven Soderbergh’s Ché). It didn’t detract from my enjoyment too much, but I feel like there’s more to tell – especially on his time as the president, which is a massive part of his life that was barely touched on.

Some of the prosthetics used to make Elba age were also a bit lacklustre. The first scene we see him as an old man is seriously undermined by the fact it looks a bit cheap. I wonder whether they thought they could get away with Elba’s appearance as a younger Mandela because we were less familiar with him, but panicked with his latter years under the knowledge that Madella’s face and appearance are so familiar.

Overall, this is a film that deserves to be seen and the box office will no doubt swell because of the timing of the release. It’s also a film heaped with responsibility that treats his legacy with due respect. Some reviewers have said that, because of this, it plays it safe. I disagree whole-heartedly. How else could this story have been told? It’s a fantastic work of art that is certainly worth seeing.

Mandella: The Long Road To Freedom is released at cinemas in the UK on 6th January 2014.