I’ve never been a huge fan of Westerns. It’s a slight bugbear of mine and I hate to be so sweepingly dismissive of an entire genre, but until recently they’ve always seemed so formulaic and lacking in unique characters.

That’s not to say I don’t have many fond memories of Westerns. My grandfather was a huge fan of any films with cowboys in. Growing up, I lived away from most of my family and so getting to my grandparents’ house was a long journey that would usually have us arriving in the early afternoon, by which point my grandfather would often be settling in to watch a good Western. At the time, the subtleties of the character development or the most intense of standoffs was undoubtedly lost on my pre-teen self.

With the trusted Master of Cinema label now lovingly releasing a select few Western films (with the typical smorgasbord of bonus material to help put the films into context), I’m giving the genre a second chance, if nothing else to prove my smarmy little 10-year-old self that he was wrong all along.

Shane tells the story of the titular hero, played by Alan Ladd. As the opening credits play out, he rides into a small isolated town in Wyoming to meet the Starrett family. He has a mysterious past but quickly wins their favour before the father Joe (Van Heflin) invites him to stay on their property to help out on the ranch.

Over dinner, he learns that the entire town is being terrorised by Rufus Ryker (Emile Meyer) and his gang, who are driving out families one-by-one to gain total control over the land in the area in order to better herd their cattle.

Thus, the story plays out with Shane and Joe forming a stern partnership to rally against the gang and save the town for those families already settled. As the conflict escalates, Shane emerges as the classic lone gunman hero in which the whole town’s hopes lie.

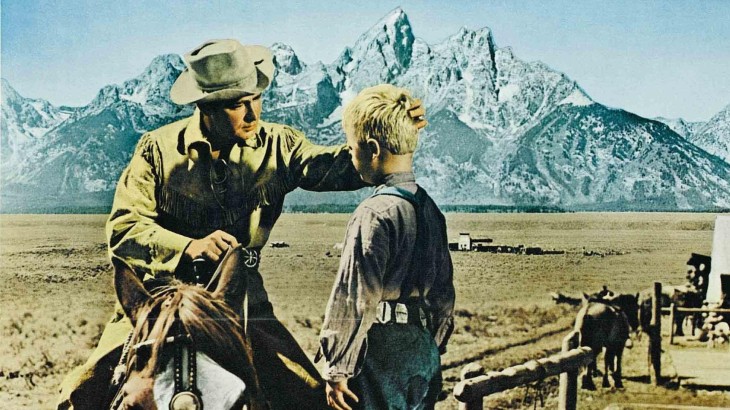

Whilst the story itself is quite familiar, befitting of any good cowboy or samurai film, director George Stevens gets away with the over-idolisation of Shane as the all-American hero by the inclusion of the young Joey Starrett (Brandon deWilde). It is through his eyes that we see everything happen. This has one of two effects. Firstly, it allows Shane to be as formulaic as he needs to be by virtue of the fact that the story can be considered as a retelling of the tale through Joey’s memory of the fact. If that doesn’t sit well as an interpretation, then at the very least the saintly actions of Shane can be seen as a means to leave a positive impression on the child – which he certainly does.

He is clearly a man wrestling with the wrongs of his past, and spends most of the film trying to hide this from the Starrett family. When he finally reveals his gunslinging credentials in front of the Joey, he decides it’s time to move on, presumably to the next place he stumbles upon that needs rescuing.

Whether he makes it to that next town is open to interpretation. Indeed, in the final shootout, he does take what looks like a fairly serious wound to the torso. He plays this down for his final leaving speech for Joey, but as he rides off I couldn’t help but wonder whether he was going to survive. After all, he’s spent the best part of two hours putting a brave face on for every other aspect of his life – he certainly wouldn’t let on to Joey that he was about to die.

The romantic subplot between Shane and Joe’s wife Marian (Jean Arthur) adds an interesting subtext to the situation. Clearly she is pining for him, and her interest is underlined in every scene they share. It feels a little shallow, and does nothing for Marian as a character as she follows every stereotype in cinematic history. Alas, it was typical of the time and her only purpose is to add some sex appeal to Alan Ladd’s handsome hero.

Shane may be a typical Western, but it is a fine and pure example of the genre that is rightly being held up as one of the best of its kind.

[Note 1] The second screenshot in this review is how the film should look on your widescreen television, with black bars down the left and right sides of the picture. This is due to the aspect ratio used (1.37:1). There is a second aspect ratio available on the disc, though as Adam Naymar explains in the booklet note “Don’t Fence Me In” this is a controversial version of the film. I’ll let you read it for yourselves should you make the purchase.

[Note 2] Below is the theatrical trailer for Shane. It is proof that cinema goers in 1953 cared not for spoilers, as the critical climax of the final scene of the film is included. Quite why this was done is a mystery to me as it completely ruins the entire film, but since the film is now 63 years old I don’t feel it is fair to be angry towards me for including it in this article. After all, I’ve given you fair warning…