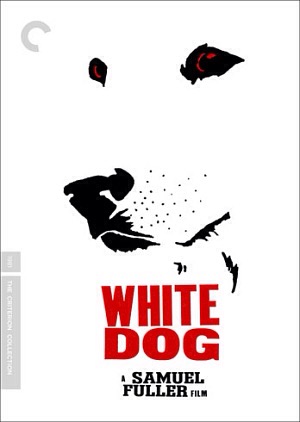

I have to say that White Dog was the first Masters of Cinema release I was genuinely disappointed with. The series, which is usually so full of care, character and attention to detail, falls short on a number of levels this time out.

Firstly, the film itself is very short, at just 90 minutes. The transfer is great, but I’m sure there was space on the disc for at least one other bonus feature. Unfortunately we get nothing – no trailer, no documentaries, no language options or subtitle options, sound only in 2.0 Digital Dolby, no discussion on why the film was banned, how the ban was lifted, how the restoration went. Not that I want to specifically compare Masters of Cinema to Criterion (though they often are), but they did get interviews with producer Jon Davison, co-writer Curtis Hanson, director Samuel Fuller’s widow Christa Lang-Fuller and dog trainer Karl Lewis Miller. The only bonus is the admittedly extensive booklet, which actually has similar contents to the Criterion release. Even the packaging on the MoC release looks lazy, and hardly goes any way to sell the film to anyone not familiar with either the film or the Blu-ray series.

The film itself is actually really intriguing. The story opens with a car accident where a struggling young actress (Kristy McNichol) runs over a stray white Alsatian. She agrees to pay the veterinary bills even though she can scarcely afford to and when nobody comes forward to claim the dog she adopts it for herself. The dog saves her from a vicious attack from an intruder in her home, which tightens the bond between the girl and her new-found companion, but it soon turns out that the dog has been trained to attack black people – a dog trained by white racists. Not wanting to give her pet up, she seeks out expert animal trainer Keys (Paul Winfield), who becomes obsessed with retraining the dog’s behaviour in what will be one of the hardest projects he will ever take on.

McNichol and Winfield give assured performances in the lead roles and the dog is given real character by some clever angles and a slow reveal of his true colours. The climax to the film is exciting, though a flip in personality for McNichol’s lead character shortly before the conclusion of the story left me with mixed emotions on how I wanted it to pan out. The biggest highlight for me was the excellent score by Ennio Morricone. It’s probably not worth a purchase just for this.

White Dog would doubtless been forgotten due to lack of interest but for the fact it was banned for so long. Another non-victory for the censors then, but no great reward for the patient film lovers that have waited three decades to see the film.

White Dog is available on Masters of Cinema dual-format Blu-ray and DVD now.